The Wheelwright Blog.

Setting the record straight…

Welcome to The Wheelwright Blog.

In this blog I want to record some of the knowledge I have found out about wheelwrighting but also to set the record straight regarding good and bad practice in today’s world.

A little update about me…

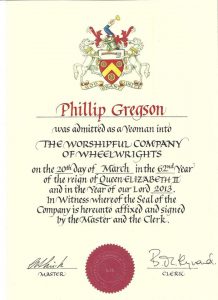

I’m Phill Gregson CF, Master Wheelwright, Yeoman of the Worshipful Company of Wheelwrights. CF stands for Churchill Fellow (granted with respect to the research I have undertaken in the field of Wheelwrighting).

It’s a bit of a mouth full I know but I’m very proud of my achievements and accreditation.

Most importantly though, as a working wheelwright, are the practical skills and abilities I have to hand, not only consisting of my own experiences from over 20 years in the wheelwright’s shop but there’s also currently over 200 years of living wheelwright knowledge in my workshop and it goes back for four direct generations. So, I would hope that I have a relative wheel making encyclopedia to hand.

The key thing is that, despite all the knowledge I have to hand, I always have a thirst for more, hence the Worldwidewheelwright project and my current ongoing research into material testing, strengths, stresses and engineering strength traits in traditional wooden wheels.

So, I think that’s enough about me for now, let’s get going…

The wooden wheel is considered by some to be one of the greatest inventions in the history of great inventions. One could argue that without the wheel we would have pretty much none of the inventions that developed since approx. 5000BC.

This may seem a bold claim, but think about it for a moment, the wheel features in everything we see around us, it heavily features in very simple early pottery and art for good reason. You probably would struggle to farm crops without the wheel, how else would you move your harvest? What about trade? How would you move your goods?

It would be difficult, if not almost impossible, to do all those things. Not to mention the related engineering principles, such as gears and pulleys, which are in pretty much all everyday items, that are in essence a wheel.

So from this we must consider the wheel as something extremely important, it’s history, but it’s present and future too.

Here’s where we get into my opinions and feelings a little deeper….

I have the ultimate respect for the history of the wheel and believe it is massively overlooked, simple remarks in articles such as “the wooden wheel remained pretty much unchanged since the roman era” or “the wooden wheel was no longer fit for purpose” make me sad as this simply isn’t true.

The wooden wheel has been an ever evolving piece of technology from day one, only being superseded in the early 1900’s by metal spoked or pressed out steel rims with pneumatic tyres due to manufacturing practices.

From the earliest disk type wheels such as the Ljubljana marshes wheel through to the chunky, round spoked, Oseberg Cart, then on to the Roman and Celtic metal bound or hooped wooden wheels that we consider similar to our wheels today. Then, with the retreat of the Romans from the UK in approx 500AD, the evolution of the wheel took a stepback for awhile and there was a spell of making spoked wheels without metal tyres. There are different opinions to the reasoning behind this but my opinion is that if iron was, at times, equal in value to the same weight in silver, then you’re not going to waste it on wheel tyres.

Some of the greatest advances in the wooden wheel came along late on in its history, in the form of dish, stagger and metal bearings.

Dish is made by angling all the spokes forwards to the outside face of the wheel and is used to give the wheel lateral strength. Most wheelwright’s don’t know how or why dish exists and some don’t consider it important at all but it is vital for a strong, working wheel to have a correct amount of dishing. I will explain dish further in future blogs and posts…

Stagger is made by having two rows of spokes, offset from each other to give lateral strength, a basic form of buttressing that allows the same lateral strength at the base or ‘foot’ of the spoke whilst utilising lighter spokes (smaller cross section). This helps make the wheel lighter and came to be quite popular throughout the 1800’s onwards.

Metal Bearings make the wheel more serviceable, capable of carrying heavy loads further and more easily, as well as enabling the wheel to be made lighter as a metal axle didn’t need to be as big as a wooden axle in order to carry the same weight.

I’ll go into all these points in much more detail at a later date as it would take a lot of writing to do each topic the justice it deserves.

Stop Re-inventing the wheel…

This is where I might start to rant a little, as you can probably see, the wooden wheel means a lot to me and up to recent years there’s always been a necessity for a wheel to be ‘fit for purpose‘. You may hear me prattle on about this a lot but it is the main function of a wheel to do the job it was intended for.

So throughout my career as a wheelwright I have seen trends in the type of work coming through the workshop doors.

There was a time when most of my work was for handcarts for local fruit and produce markets but they’re mostly closed down now thanks to the likes of supermarkets and online shopping. In a busy year my family firm could turn out up to 200 new and/or restored handcarts.

Then there was also a spell where I couldn’t make enough Gypsy wagon and dray wheels. Sadly, I can’t compete on price with cheaply imported sets from Poland these days, however, they could probably never compete with me on quality. To list just a few faults (a few of many); their tenons are too narrow and short which weakens the spokes laterally; the nave/hubs are too small leaving little supporting timber between the spokes; the whole wheel is produced from ash, not the traditional oak, ash and elm or even suitable alternatives; the tyres are often not tight enough and the welds/joins are regularly not filleted out before welding (so the tyres snap after a little wear on the road) and that’s not to mention the soft iron axle boxes (bearings) that seize solid onto the axles then churn their way out of the wheel, which in my opinion is one of the most dangerous points about these wheels… (deep breath and carry on)…

The next big thing that now keeps me busy is replacing the poorly made imported wheels mentioned above and the incredibly poor quality wheels made in the UK too!

My current work load is made up of around 50% repairs/replacements, of which probably half again are relatively new wheels made to an unacceptable standard.

There’s many things that anger me around these facts, I could probably write a long list but just a few of the main points will do for now.

Badly made wheels will be the death of Wheelwrighting in the UK…

Recent years have seen an increase in the amount of wooden wheels replaced by aluminium or steel wheels. Why? Because people don’t believe that wooden wheels can be fit for purpose, despite having had original wooden wheels that have lasted around 100 years. I believe this is because they have then had them repaired by an “wheelwright” to soon collapse or become very loose. The response from the “wheelwright” is “what do you expect? it’s a wooden wheel” as a way to cover the fact that their work is unacceptable and customers sadly believe them because “but they do the work for (insert respected organisation here), so they must be good“.

Luckily some of these customers make their way to my workshop instead of giving up or heading to an aluminium foundry. Although, unfortunately, by this point they have been ripped off by the previous “wheelwright” and some are thoroughly put off from having wooden wheels again in the future. One example that sticks in my mind is a comment on a Facebook post recently stating “don’t waste your money on anything with wooden wheels, you’ll be replacing the wheels every few years“. This shouldn’t be the case, I would certainly be disappointed if any wheel I made did not outlast me, if suitably cared for.

One very sad example of how poor craftsmanship is effecting the future of the wooden wheel is … The recent carriage that was gifted to the Queen for her Diamond Jubilee by Australia has aluminium wheels, described to have been chosen “due to the high cost of producing and maintaining wooden wheels“. To me this seems like one of the biggest death blows to the wooden wheel and I question what is to blame? and how we have been brought to this position? I know that these decisions and costings are not black and white but I really struggle to see how this can be the case, as above I would be extremely upset to have to revisit one of my wheels in my lifetime.

The wooden wheel…several thousand years in the breaking…

So what are the bad Wheelwrighting practices that are going on in the UK?…

There’s a long list of bad practice going on, most of which a trained eye can spot from a mile away.

Loose/poorly fitted joints… All the joints on a wheel should be tight once the tyre is on and the spokes should actually be tight into the nave/hub before the tyre is fitted. If you want to see examples of poorly fitting spokes simply Google ‘wheelwright’s in the UK’ and take a look at the photo galleries on websites, there are some shocking examples of work being showcased… hint… if there’s a gap down a mortice or under the shoulder between the spoke and the nave/hub then it is wrong. In my workshop the spoke tenons are made oversized and tapered, then driven in with a sledgehammer, no toffee hammers or just pushing them in with a bit of glue here.

If the joints aren’t tight then the wheel is compromised considerably, it may not be safe to use. It is Not fit for purpose.

Wrong wood choice… There’s some very important reasons why we use the woods we use in a wheel. Elm doesn’t split easily so we use it for the nave/hub as it resists splitting to pieces when we drive the oversized spoke tenons into the mortices. There are few suitable replacements for elm and I only recommend substitutes when absolutely necessary (I use utile as it has a similar interwoven grain to elm but it is completely unsuitable for other parts of the wheel due to its low cross grain strength and medium crush strength).

The spokes are made from oak (or hickory in the case of some American, mass-produced wheels and beech in some military wheels due to only having a low life expectancy and not lasting long enough to rot). George Sturt wrote in his famous book The Wheelwright’s Shop of spokes being “invariably of oak” and for good reason, oak doesn’t bend or distort under load and lateral forces, so the wheel stays upright, rigid, true and strong. If the spokes flex or bend, the forces aren’t kept between the wheel components, the wheel becomes loose and therefore compromised/unsafe or Not fit for purpose.

The felloes (curved outer segments) are pretty much always made of ash in the UK although I have seen some alternatives such as beech, wych elm and oak used on old wheels, they tend not to have lasted well. We use ash because it is springy, it gives the wheel a basic, built in form of suspension and stops any shocks from the road destroying the wheel. These excellent properties mean that ash is not suitable for other parts of the wheel. I’m seeing a lot of cheap, imported hardwoods such as seraya used to replace felloes. This is one of the worst choices of wood for any part of the wheel as it has a medium crushing and bending strength combined with low shock resistance and poor resistance to decay. It is very cheap and is often cheaper than good quality softwood. It seems to be a simple matter of profit driven corner cutting. One example of why people use these woods is “I just tell them it’s mahogany, then they think it’s good quality” or “they never know the difference when it is painted” well personally I think you should be reported to trading standards as you are ripping people off, not to mention it is not fit for purpose.

“Mahogany Wheels”

Don’t be conned by the story that they’ll make your wheels from “mahogany” when in truth most cheaply imported, red coloured woods from West Africa are labelled as a “false mahogany” or “african mahogany”. True mahogany is subject to import restrictions and generally unobtainable in the UK. People often unfortunately confuse the word ‘mahogany’ as a sign of quality like using “solid oak” when in fact every timber has its strengths and weaknesses, which make them suited to specific purposes.

We have been using elm for naves, oak for spokes and ash for felloes for thousands of years for good reason, if the Victorians thought that “mahogany” was better for wheels then they certainly had plenty of it and would have used it.

So maybe I prattled on a bit too much for one little blog, but, I do feel it is important to get people up to speed with the issues we face today.

I’ll do my best to make the next blog a little more interesting and focused on interest points around the wheel as well as my current work load.

If you have taken the time to read this, thank you for paying attention!

Phill